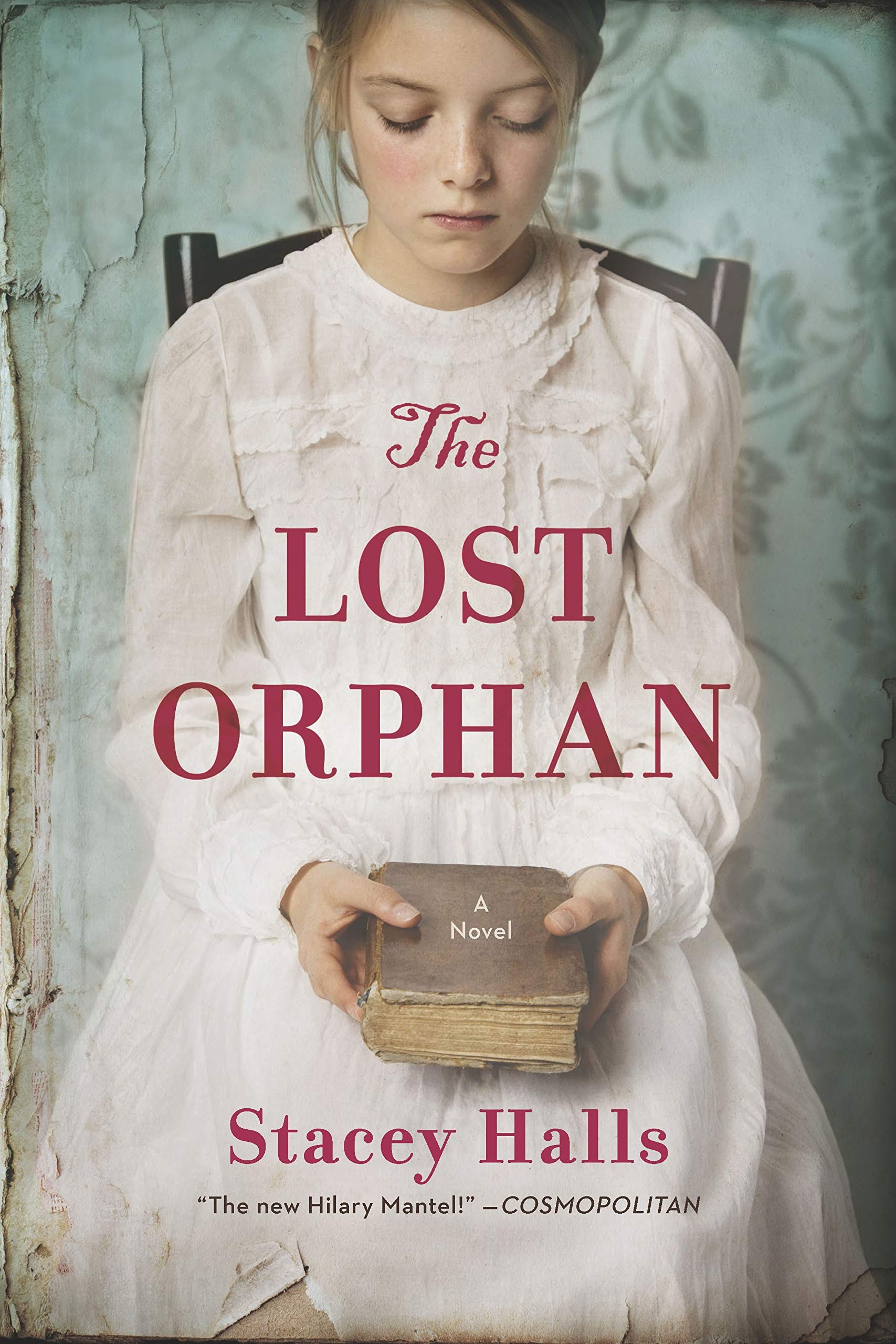

The Lost Orphan

Blood and water mix in The Lost Orphan (Mira) by Stacey Halls. This novel, which takes place in 1747, could just as easily been titled “A Tale of Two Mothers,” with a respectful nod to Charles Dickens’ novel set similarly in Georgian London three decades later. Clearly, in both stories, “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times.”

Blood and water mix in The Lost Orphan (Mira) by Stacey Halls. This novel, which takes place in 1747, could just as easily been titled “A Tale of Two Mothers,” with a respectful nod to Charles Dickens’ novel set similarly in Georgian London three decades later. Clearly, in both stories, “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times.”

In Halls’ story, Bess is dirt poor and unwed when she gives birth to a baby girl. With no ability to care for her daughter at that time, she surrenders her to the Foundling, a hospital for unwanted babies.

Fully intending to return in the future when she’s earned enough money from her shrimp selling job, Bess leaves a token—half of a heart-shaped whalebone—to identify Clara. The child’s father has the other half.

When she returns to Foundling six years later, Clara is gone. Not dead, but claimed by someone posing as Bess the very day after she’d left her there.

Meanwhile, Alexandra is an eccentric widow of means, with a seven-year-old daughter named Charlotte. Each afternoon Alexandra takes tea and has idle chit-chats with her deceased parents. When she asks them why London needs three bridges across the river, when one is enough, her “mother smiles placidly.” A recluse beyond imagination, Alexandra tries to instill her myriad of deep-rooted fears of intruders on her young daughter, home-schooling her and allowing her to venture outside only for church services.

Encouraged by a family doctor who works at Foundling, Alexandra acquiesces and opens her home to a stranger—a young nanny named Eliza. Finally, though much to Alexandra’s despair, Charlotte has a playmate, someone to share her bedroom with, someone to dote on her.

But these two women are not what they seem. One is water, one is blood; and their secrets could well be their undoing, placing the innocent child in the middle of a nightmare.

As you’ll see in the interview with the author below, Halls intended to upend the “monster in the house” genre. And she overachieves because there are two monsters, not just one; and we, the reader, sway from cheering for one mother and then the other.

Though Halls transports us back to an era we’ve read about before, her vivid and graphic descriptions become almost holographic. We see the ratty blankets, food scraps, the seedy side of London. We smell her brother relieving himself in a pail. We grasp why Bess is thought of as a whore, though she is not.

Moreover, Halls’ characters are well rounded, coming alive and distinguishable by their words. Alexandra and the good doctor speak the King’s English, whereas Bess’ down-trodden family and friends embrace the jargon and slang associated with that era.

Even though the core of the story is the tug-of-war between Bess and Alexandra, ultimately we root for The Lost Orphan to win.

Interview with Stacey Halls, The Lost Orphan

What inspired you to write The Lost Orphan?

My story ideas come from places. This one came to me when I visited the Foundling Museum in Bloomsbury, London. I wasn’t looking for a story idea; in fact, I’d just finished the first draft of The Familiars the week before. But I was so moved by the museum and the concept of the Foundling Hospital, which was established in the 1730s for babies at risk of abandonment.

I was particularly moved by the tokens left by mothers who hoped one day to claim their children. The tokens were like secret deposits that only the mothers knew about and would describe to prove their identity if they ever found themselves in a position to claim their child however many months or years down the line. All the objects were worthless scraps of fabric, coins, playing cards, except because they were the only things connecting the mothers with their children, they were priceless.

After my visit, I decided to write about a woman who had saved enough to buy her baby back only to discover her daughter had already been claimed.

Similar to your first novel, The Familiars (Mira, 2019), set during the 17th century Pendle witch trials in England, this story also features two women who are polar opposites. With two strong protagonists, who or what do you consider the antagonist in The Lost Orphan?

I was interested in writing about two women who don’t understand each other, and I wanted to go deep under the skin of both of them. So often all we have is our own perception, and I wanted to explore how they both saw the same situation. As such, they are each other’s antagonists. Certainly, Alexandra has more issues than Bess, but I was also interested in turning the “monster in the house” trope on its head, where the narrator doesn’t know there’s a monster in the house, and the reader knows more than her.

The Foundling Hospital existed for two hundred years. Why did you choose to set this novel in the mid-1700s soon after its founding?

Lottery night, where women were invited to draw colored balls from a bag while wealthy revelers watched, formed the admissions process in the Hospital’s early years. The color of the ball determined whether or not their child was admitted. A white ball meant their child got a place, red put them on the waiting list, and black meant they’d lost. This striking image just had to be in the first chapter. Also, I wanted to include the tokens that were used in the Georgian period.

Your description of London in this period is evocative, haunting; and your dialogue lively and distinctive. What resources did you access to bring the setting and characters to life?

It’s about immersing myself in the place I’m writing about. I turned to maps, diaries, biographies and non-fiction that focused on Georgian London. Two books that proved immensely helpful for building a picture of what the city was like at that time were Georgian London: Into The Streets by Lucy Inglis; and William Hogarth: A Life And World by Jenny Uglow. I also live in London, and the blueprint of the Georgian city is still very much there. The courts and alleyways of Bess’ London aren’t, but the townhouses of Alexandra’s Bloomsbury are.

Any chance you’re writing a sequel to The Lost Orphan? If not, will your next project propel us into the 19th century?

A sequel is not in the works, but I’m writing my third novel, which is set in Edwardian West Yorkshire. So I’ve skipped forward about 150 years. They had cars and phones by then, so the period feels very modern to me!

.png)

_w200_h/Taylor3_Front%20Cover%20(2)_03040543.jpg)